Speech

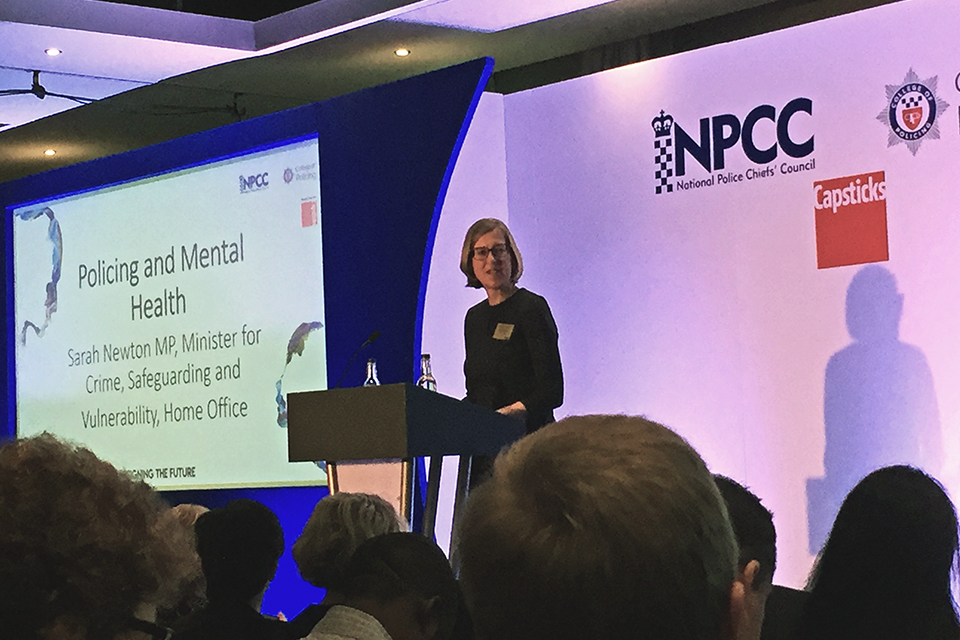

Sarah Newton speech at mental health and policing conference

The Minister for Crime, Safeguarding and Vulnerability was speaking at the joint National Police Chiefs Council and College of Policing conference on mental health.

Podcast behind bars with a mental illness

BBc News broadcast 15 September 2017This is a full transcript of 'Behind Bars with a Mental Illness' as presented by Damon Rose and Beth Rose

This is a full transcript of 'Behind Bars with a Mental Illness' as

DAMON- This is Inside Ouch, I'm Damon Rose and with me is Beth Rose - not related.

BETH - Hello, have to clarify that, yeah.

DAMON

- Always have to say that. This week prisons and mental health have

been in the news a fair bit. You may have heard of the case of James Ward

that has been in the headlines in the past few weeks. He was the man

who was jailed for 22 months but ended up doing an 11-year sentence from

2006 and has just been let out. And this was due to IPP, imprisonment

for public protection. And also the London Assembly have completed a

report on the welfare of prisoners with mental health difficulties and

after prison care.

Everybody's experiences of prison are

different, and earlier we spoke to Ria who had mental health

difficulties which led her to being put on remand for five months in

prison. And we'll hear all about this from her in a second.

But before we go into it we should say that there

are some quite distressing moments in this interview which talk about

suicide and psychosis, and if this isn't the kind of thing you want to

hear at the moment please do turn off and come back to us again next

week.

Here's the interview, this is Ria:

RIA - I ended up

in prison because I had a psychotic breakdown and that culminated in me

setting my house on fire, and I was charged with arson, recklessly

endangering life, and sent to prison on remand.

DAMON - You were

unwell. I think a lot of people would be perhaps surprised or confused

that you weren't put into hospital at that time

RIA

- It was 12 years ago; I have no idea in what way things are different

now, if they are different. Yeah, people would be surprised, but prison

is full of people with mental health problems so it's not unusual.

BETH

- At the time did no one speak to you about your current health

situation or whether you should go to the hospital? Were you just taken

straight to the police station?

RIA - I was taken straight to the

police station. While I was there I did have three assessments with

three different medics. I have no idea what those assessments were

about. I think they were about whether I was in a fit state to have a

police interview. I can't tell you if there was any thought of me going

to hospital. I was not in a good state myself; I didn't really know what

was going on.

BETH - I've not been in that situation myself, but

do they give you access to a GP or anything? Because it seems if you're

in that kind of situation and you're not really sure what's going on

and no one's explaining, and quite evidently you're not acting as you

normally might, that there should be some kind of intervention at some

point.

RIA - Yeah, there was definitely not any kind of

intervention beyond these three different assessments where I was asked

questions that I didn't really understand and found very confusing. I

had to shout all my answers because there was so much going on in my

head, so much noise and confusion that the only way to speak was to

really hold on very hard to one chain of thought and kind of force it

out of my head.

I mean, I've pretty much had mental health

problems all my life kind of on and off, or meaning there are times

within that where I function better than others. And at this particular

point in my life a very close friend of mine from childhood had taken

her life a year previously and this had a massive impact on me.

Ultimately I had a psychotic breakdown through dealing with my grief

over her suicide.

Being psychotic is a bit like being in a dream

where all the rules about how the world works are different, anything

can happen. I'd been unable to eat because I thought I was being

poisoned. There was a lot of energy in my head and the only way to deal

with that was to walk a lot. I thought people were following me. I had

to paint out my windows because I thought satellites were spying on me

from the sky. It was a very frightening time.

DAMON - People

perhaps think that you're perhaps born a little bit, I don't know, more

vulnerable to these kinds of things. But from my experiences over the

year often it's an incident like a death that can bring on something

like this, experiences that you've never had before.

RIA - Yeah,

my psychosis was totally wrapped up with my grief and my friend, and

things to do with my own life too, but yeah, it was triggered by my

friend dying.

One of the things that was happening for me was

that I was incredibly volatile, which is not something I'd really

experienced before. So, I was just having really overwhelming emotions

that I couldn't really control or contain. There was one day that I was

walking down a road and I was just so angry that I jumped on every

single car in the road, and then I picked up bricks and rocks and I

started throwing them at people's houses, at their windows. And a bit

further down the road there was a woman with a toddler and I saw her

kind of clutch him to her and go in her gate and shut the gate and

quickly go into the house. And seeing this kind of brought me down a bit

and I just thought, wow, she thought I was going to hurt her! Of course

she thought I was going to hurt her, like I was throwing bricks around.

And it just horrified me that someone would think that, that I would

frighten someone like that. So, I got myself home and when I got home I

just decided that's it, if I can't control what's happening for me then

I'm not safe and I won't leave the house again.

DAMON - How long after this incident was it before you set light to your house?

RIA

- I'd say a few days. I don't know really but I'd guess a few days. I

was very frightened still. I used to sleep in my airing cupboard because

that felt like the only place that was safe. And then one day I just

thought okay, I do have to kill myself, that's the only way I can get

out of this situation. And there was a bit of a release in that I

suppose. I spent a few hours running around my flat trashing everything

because nothing mattered anymore. And I knew that I had to die by fire

because I felt that I was poison and everything I'd ever touched was

poison and if I needed to leave the Earth I needed to leave any trace

that I had ever existed.

Another thing that was happening was I

thought people were reading my mind, I thought I was being assessed by

social services, I thought that they had got people out of the house.

And because they knew and they hadn't stopped me I understood that as

permission because killing yourself is not illegal - obviously setting

your house on fire is, but I didn't really think about that. So, yeah

that's the day that led up to it.

DAMON - And so you set the house on fire. Can you tell us about that?

RIA

- Yeah. There was a pile in the corner that was my kind of worst things

that had to go, the things that I did not want anyone to see. They were

things like things I'd written, pictures I'd drawn; I felt like these

were the things that were full of my poison and needed to be eradicated

so that's where I started the fire. And it went up really quickly. It

was quite shocking. I remember running to my flat door and shouting,

"If

there's anyone in the building I suggest you get out now" and I went

back in the flat and I locked the door and I watched the fire for a

while and I got very frightened and I phoned my friend and I told her

what I'd done and she told me to get out, and I wouldn't. At some point

in had to go into the bathroom because the fire had got so big that that

was the only place I could be. And she did eventually convince me to

get out but it was too late to get out through the door by then so I had

to climb up onto the roof, and the fire brigade rescued me off the

roof.

BETH - When the fire brigade rescued you on that evening did you basically get taken straight into police custody from then?

RIA

- No, when I came off my roof half my street was out there, some of

them taking photos. I couldn't cope with being looked at like that so I

just walked off round the corner and sat on the wall and waited to be

arrested; like I knew that was what was going to happen. So, yeah, the

police found me there and arrested me there.

BETH - And they didn't even take you to like accident and emergency or anything?

RIA - No.

BETH - Which is really shocking in itself, someone who's been rescued from a fire and then taken straight to custody.

RIA - Yeah.

BETH - You had your friend with you, did you?

RIA - Yeah.

BETH - And was she able to talk and try and explain the situation to the police?

RIA - Yes she did talk to them and she was there with me. They even let her in the police cell with me, which I think is quite unusual, but I was so distressed. But once you're in that system there's not much can be done really, there's a series of stages you go through; there's not really anything that can deviate from that.

BETH - It just seems really difficult to comprehend that someone in such an obvious state of ill health can just be put in a cell and just put in a system that seems unrelenting until you end up in prison ultimately.

DAMON- After this point. And what were you charged with?

RIA - Arson, recklessly endangering life.

DAMON- And this is when you were put on remand?

RIA - Yes.

DAMON- So, they didn't allow you home. You went to a prison.

RIA - yes.

DAMONAnd what happened when you got there?

RIA - I got sent straight to the hospital wing. Yeah, I was terrified. I'd never been in prison before, and the stories out there about what prison is like are not very accurate, but how would you know that when you first arrive and are psychotic and struggling to work out what's happening and what isn't happening anyway?

I ended up on the hospital wing which is a small unit, it's very noisy, it's full of very distressed women, there's a lot of crying and shouting.

DAMON- And there was one particular shout that you heard a lot from one person, wasn't there?

RIA - Yeah, there was one woman who pretty much, it went on pretty much 24/7 and it reverberated all around the wing, she would just pound on the door of her cell shouting, "He's a paedophile! He's a paedophile! He's a dirty [swears] paedophile!" And I was so sound sensitive at that point and these words I just felt them pounding into my bones.

BETH - You say it's like a hospital wing; did you get good psychiatric and other healthcare or is it just a name for another section of the prison?

RIA - It's just a name for another section of the prison. [Wry laugh] That's maybe not fair. I didn't get any kind of treatment while I was in the hospital. I did get a little bit of support; there was a CPN, a community psychiatric nurse - I think they might have a different name when they're in prison - who would come and see me, and she was kind. And yeah, kindness is really important all the time, but in prison where there's so little kindness it does make a difference. But I didn't see a doctor or anything like that.

BETH - And before prison did you have a medical plan in place? Were you on medication or did you see counsellors?

RIA - No, I wasn't on medication. Leading up to the fire I had seen my GP. I had asked her to be in hospital. I said, "I'm not safe" and she had told me that these days people are much more often looked after in the community; which is fine, like hospitals are pretty horrible places, but it's very hard to keep an appointment when you don't know what year it is, never mind what day of the week or what time it is.

One of the beliefs that I had at the time was that everything going on around me was a simulation that people had put in place for me to learn something. And I was sat on the prison wing waiting for my friends to stop this particular simulation and say, "It's okay, she's learned enough now, we don't need to keep doing this". And I think at some point I just realised that wasn't going to happen and that I was in prison and that this was my life now and if I was going to be able to cope with what was happening I needed my head to work like it used to work. And I just did everything I could to try and get my head back again. For me that meant I'd pace my cell to try and burn off some of the energy. I did an awful lot of writing; I did lots of drawing; I'd sing. I did a lot of maths; that's something that helped my head. [Laughs]

BETH - Just maths that you came up with yourself?

RIA - No I asked for a textbook, because there was just something really reassuring that I could still do maths, like that part of my head still worked.

BETH - And then did that all stop after your months and you were transferred back to the main prison?

RIA - Yes.

BETH - And you were just kind of left in your cell to get on with the menial tasks?

RIA - Yes.

BETH - And did that impact the progress you made or had you got yourself to another state where you were able to keep progressing?

RIA - Well, I did come round from the kind of most acute phase of my psychosis. That happened before I left the hospital wing; that's why I left the hospital wing. But my experience of being on the main prison and not being psychotic was actually it made me really depressed. While I was psychotic I actually had quite a lot of tools that I could use to cope with what was happening. For example I could project soothing images onto the wall to look at. My mind was very malleable. And once I couldn't do that anymore I was just very aware of how bleak my surroundings were and how much distress I was sitting around. It was a very difficult environment to be in and I was very depressed.

DAMON- So, you tried to take things under your own control and burn away some of the energy and things like that. Was this something that continued, were you trying to help yourself further during this period?

RIA - Well, I was still able to do that by I got a job as a wing cleaner, which is quite a physical job, so that helped.

DAMON- After was it five months you were allowed to leave?

RIA - Yeah. One of the things about prison is communication is really difficult, so I had no idea that my solicitor was going to court to get me bail. Someone just opened the cell door one day and said, "You're going home - now". [Laughs] So, yeah I was released. My friend was waiting for me; I went and stayed with a friend while I waited for trial.

DAMON- And you didn't have a home?

RIA - No, I didn't have a home.

BETH - And what happened when it came round to the trial? Was it a long drawn-out process or was it quite quick?

RIA - It was very quick. After the first morning the judge took my solicitor and my barrister into chambers and said, "You need to tell her to plead guilty and if she doesn't plead guilty I will direct the jury to find her guilty and I will send her to prison". So, I changed my plea.

BETH - Wow! And was there any mention of your mental health at all?

RIA - Not at that stage. My mental health came up at sentencing as a kind of mitigating factor.

BETH - And what was the result of the trial?

RIA - I was sentenced with a three-year community order including psychiatric supervision.

DAMON- So, you regularly had to see a psychiatrist?

RIA - Yeah, I had to see a psychiatrist and I had a community psychiatric nurse as well.

DAMON- And how was that?

RIA - [Laughs] Well, as far as I'm concerned it hindered my capacity to get on with my life. I'd been diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder by this stage but I was doing really well; I wasn't psychotic, I wasn't in the state I was in before I set my house on fire. The psychiatrist said that I had to take medication to cover his back, and I asked him that my treatment be based on my needs rather than what might happened to him if it goes wrong, and he just laughed and said any psychiatrist would medicate me. So, I ended up on antipsychotic mood stabilisers and antidepressants. They're horrible drugs, they're toxic; they have horrible side effects. For me I didn't really start getting on with my life until I'd finished my psychiatric supervision and could take myself off the medication.

DAMON - And that was what, three years later?

RIA - It actually didn't last as long as three years in the end. I think it was something like 18 months because I was doing okay.

BETH - And how has all of that impacted on your life now, sort of 12 years on or nine years on?

RIA - It's something that always comes up if I ever go for a job. My conviction is spent which means that I shouldn't have to tell people, but I usually work for the kind of jobs that require enhanced police - it's not CRB checks anymore - DBS checks where you have to declare everything. So, I have to say, "Yeah, once I burnt my house down" which sounds terrible, so then I have to say, "But I had mental health problems at the time", so then it's like you can discriminate against me for being a criminal or you can discriminate against me for having mental health problems, take your pick.

BETH - And what kind of job or jobs have you gone on to do with these increased DBS checks?

RIA - I'm not working at the moment because my mental health is bad right now, but up until a few years ago I worked as a children's counsellor.

BETH - Was that for specific childcare needs or mental health or anything?

RIA - I worked mostly in schools just with kids who had various difficulties.

BETH - Do you think your experience of the system or maybe despite the system helped you in that role?

RIA - I don't know really. I think I'm probably much less judgemental than I might have been had I not been through that experience.

DAMON- And that job I think a lot of people would be quite surprised to hear that you were able to gain the trust of an employer who would allow you to work with children and be a counsellor.

RIA - Sure yeah. I'm good at what I do, and obviously I had to find a way to demonstrate that. But once one person has agreed to it, once one person has decided they'll take that risk, it's a lot easier because I can say, "Yeah, once I burnt my house down but I've done this since and this person will vouch for me".

DAMON - But you're not too well at the moment you say?

RIA - No.

DAMON- And you're being looked after?

RIA - [Laughs]

DAMON - Are you looking after yourself?

RIA - I'm just laughing because in terms of support for people with mental health problems there's not a lot out there. I'm doing okay. I find my own way; I find my own way of getting help and support generally.

DAMON- Has that experience in prison been a very bad experience that has affected the rest of your life negatively?

RIA - I'd say yes. I don't know. It's a bit dramatic putting it like that but it was the most…

DAMON - How would you put it?

RIA - I always say prison was the most soul-destroying experience of my life. But the other option might have been that I end up in hospital. And at least if you go down the criminal justice route you end up with a fixed sentence, or most people do or do now, and there's an end point; whereas if I'd been diverted to hospital at that point I might still be there now.

BETH - We should just reiterate that Ria's story relates to 12 years ago. But if you've got your own experience then please do get in touch because we do love to hear from you. And you can get in touch in a variety of ways: we're on Facebook at bbcouch; we're on Twitter @bbcouch; you can of course email us and that is ouch@bbc.co.uk; or if you just like to see more of our stuff then visit our website, it's bbc.co.uk/disability.

Can probation Services Deliver? 2017

For today’s post, I have reproduced in full a recent (19 September 2017) speech by Probation Chief Inspector Dame Glenys Stacey on what is wrong with the probation service and what the Inspectorate aims to do to try to get it back on the right path.

Probation matters

Well over a quarter of a million people are supervised by youth offending and probation services each year. Many under probation supervision are not receiving the quality of services that they should, and yet we know that good probation services can change their lives and life chances.

Good youth offending and probation services also make a big difference to society as a whole. If all these services were delivered well, then the prison population would reduce, there would be fewer people sofa surfing or sleeping or begging on the streets, and fewer confused and lonely children and young people. Men, women and children currently afraid of assault could lead happier and safer lives, and yes, there would be less reoffending. These things really do matter – to those under probation supervision, to all of us working in criminal justice, and to society as a whole.

A lack of quality

But probation services are not being delivered consistently to the standard we expect. The National Probation Service, responsible for those assessed as high risk, it is delivering to an acceptable standard overall, although there are inconsistencies in the quality of work across the country, and some anomalies as well.

The majority of individuals, however, are categorized as medium or low risk, and although there are exceptions, the Community Rehabilitation Companies responsible for their supervision are not generally producing good quality work, not at all. Probation reform has not delivered the benefits that Transforming Rehabilitation promised, so far.

We rarely see the innovations expected to come with freeing up the market, and instead proposed new models, new ways of delivering probation services on the ground and supporting them with better IT systems have largely stalled. The voluntary and charitable sectors are much less engaged then government envisaged. Promised improvements in Through the Gate resettlement – mentors, real help with accommodation, education, training and employment for short sentence prisoners – have mostly not been delivered in any meaningful way. And too often, for those under probation supervision we find too little is done by CRCs. On inspection, we often find nowhere near enough purposeful activity or targeted intervention or even plain, personal contact.

Why is this?

Staff morale, workloads, training and line management are highly variable and need to improve if probation is to improve. Staff are change weary and more than that, too many are too overburdened with work. Their employing companies are financially stretched, with some unable to balance the books, as unexpected changes in the type of cases coming their way have resulted in lower payments than anticipated.

What to do?

The government must face this squarely, knowing that CRC contracts are currently set to run until late 2021. It must consider its options, in order for there to be any prospect of consistently good probation services nationwide.

Of course, these companies strive to meet performance targets set by contract – just as they should. That is the nature of contracts. Many achieve well against some of those targets, but often enough this is at a cost to the quality of work and the more enduring expectations we all have of probation services.

To give one example, CRCs commonly produce timely sentence plans, and so meet contract expectations, but those plans may not be good plans, comprehensive plans, based on a comprehensive assessment.

What is more, we find too often that despite sometimes heroic efforts by staff,

Measuring success

You would think at first sight that changes to the contract specification would do the trick. But the work that probation services can do locally, with local partners, to deal with complex, sometimes longstanding social problems and some of the most troubled and troubling people in society, so as to make a difference to those individuals’ life chances, this is very difficult to exemplify and then ensure, in a set of performance targets or measures.

This measurement problem is not unique to probation. Other caring professions may be equally difficult to measure, to quantify in this way, and for these type of services, independent inspection has a particular role to play.

For such services – probation services delivered in the community or perhaps services caring for the elderly in a care home – nothing beats stepping over the threshold, and looking with an experienced, wise eye at what is going on. In that way, independent inspectors can report objectively and faithfully how things are. They can hold up a mirror and reflect the simple, unadorned picture they see. That is what we do. But that alone does not drive improvement where it is needed, necessarily. Yes, we make recommendations and expect them to be followed, but that is not enough.

For probation services to improve where needed, a number of other things must happen. Firstly, government must – and it has started to do this – it must address the immediate funding issues, and do so carefully and wisely so as not to fall foul of contract law, so as not to create perverse incentives, and instead to secure more professional staff and specialist intervention services where needed.

Government must also make a plan, have a strategy for how probation services are to be delivered over the next decade. CRC contract end dates are not so far off. And meanwhile it must be as clear as possible about what it expects of probation services, and rebalance the oversight model, the way probation services are overseen, so as to focus squarely on those expectations.

It seems obvious to me that government should expect consistently good quality probation services, so that the public are sufficiently protected, individuals serve their community sentences productively and reoffending is reduced. For me, the problem arises underneath these enduring expectations of probation, as with Transforming Rehabilitation, probation providers were liberated from what were rather processy national standards so as to enable them to innovate.

As a consequence, and without good and commonly accepted national standards there is some confusion about what good looks like – what represents good probation services, and what is expected of probation services, actually. It is time to clarify that, and to fill that gap.

New standards

With government’s backing, we at HMI Probation are developing underpinning standards for probation services. They are not processy. Instead they are evidence based and take the best from international standards. We are developing these standards in a consensual way, working with the NPS and CRCs in particular – as they need to accept and adopt these standards with us, in order to make a difference.

We will inspect against these standards in due course. More than that, we will use them to describe what ‘good’ looks like, to provide some stakes in the ground, ways in which probation providers themselves can see where their services meet expected standards and where they need to improve.

So for example, we can be clear what good Unpaid Work looks like, and what outstanding Unpaid Work looks like – and what is plainly inadequate.

Ratings scale

And as we inspect we will rate NPS divisions and CRCs on a four point scale à la Ofsted:

- Outstanding,

- Good,

- Requires Improvement, and

- Inadequate

Driving improvement

We will do this because research shows that ratings drive improvement in immature or poorly performing markets. In other words, we think it will drive improvement where it is needed, and recognise and applaud good work when we see it as well.

To rate probation providers fairly, we must of course publish our standards and be clear how we will apply them, and of course we will do that, starting with a consultation in November. But we must also be sure of our judgements of probation providers and be sure they are fully reflective of a good evidence base in each inspection.

We will increase our case sample sizes so as to give us an 80% confidence level in case inspection findings, and we will inspect whole CRCs and whole divisions of the NPS. We will routinely inspect not just the long established areas of probation work, but new areas as well: Through the Gate work for example.

And because probation services are still volatile, we will inspect each NPS division and CRC annually, from the spring of next year.

We think that this increased emphasis on independent inspection, and standards will begin to rebalance the way probation providers are overseen. It will make clear what is expected of probation providers, and I have no doubt that most if not all providers will want to attain good independent inspection ratings.

Incidentally, I know that many across the range of criminal justice and wider public services will have mixed views about inspection, about being inspected. Some find it extremely burdensome, and in some services there is an industry in mock inspection, and preparing for inspection. Of course we expect organisations to be ready for inspection, but we don’t encourage over-prep.

We can often see, you know, the wet paint.

Inspectors have generally been inspected themselves, in their former lives, and know the game. I do urge against any overly enthusiastic approach to preparing for inspection. As HMI Probation will be inspecting annually, it is perhaps best to be proportionate in preparing for it, and then take it as it comes – something I will be stressing with probation leaders.

A co-ordinated approach

As I have said, I think our development of probation standards and more regular inspection are positive developments, capable of driving improvement where it is needed, but without further changes, the water remains muddy.

CRCs could feel conflicted, with our inspection standards on the one hand and then contract requirements on the other. And many remain financially stretched. Two additional things need to happen, in my view, to give us all the best prospect of success.

Firstly, CRCs must be put on a sufficiently stable financial footing. I have no doubt this is not straightforward: existing contracts and contract law must necessarily constrain matters, and there is a trick for government to pull off, if CRCs are to better funded and at the same incentivised to produce quality work.

And that for me is the second requirement – incentivisation. CRCs could be incentivized to produce quality work, exemplified by higher order HMI Probation ratings. For those achieving higher order ratings, there should be some recognition of that, and reward as well. That may come for example in the way they are then overseen, perhaps by a reduction in the overall oversight burden. Rewards don’t always have to be monetary, as we all know.

We are talking to government about these things. We are hopeful that government will find ways to incentivise and reward higher order HMI Probation ratings. And meanwhile we continue to inspect and report, while developing and agreeing new standards for probation that should over time mean that more people receive good quality probation services, to benefit them and society as a whole.

http://howardleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/London-Assembly-health-committee-submission-on-headed.pdf

Analysis of deaths in custody in England and Wales

http://howardleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/updated-final-Analysis-of-deaths-in-custody-in-England-and-Wales-2016.pdf

Response to the Sentencing Council’s consultation on breach guidelineshttp://howardleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/final-breach-on-HL-headed-paper.pdf

Event 1

How can we reduce violence and end deaths in prisons? This free all-day conference will bring together experts in criminal justice, prison reform, politicians, academics, officials and journalists to seek solutions. Lunch provided.

The event will also see the launch of a new report by the Runnymede Trust and the University of Greenwich into prison violence and deaths.

Book now!

Thursday 19th October. 9.30am - 4.30pm, at the University of Greenwich, Old Royal Navy College, SE10 9LS.

Panels:How can we reduce deaths of people with mental health issues in custody?

How can we reduce use of force in relation to BME prisoners?

How culturally-aware interventions can reduce reoffending rates of BME prisoners.

What role can prison officers play in reducing violence and deaths in prisons?

Steve Reed - MP Croydon North

Frances Crook - Howard League for Penal Reform

Steve Gillan - General Secretary - Prison Officers Association

Patrick Vernon - Black Thrive

Professor Darrick Jolliffe - Professor of Criminology, University of hGreenwic

Dr Zubaida Huque - Research Associate, The Runnymede Trust

Deborah Coles - INQUEST

Date and Time

Location

Event 2

COULD YOU DO TIME? Putting your faith into action in our prisons or helping ex-offenders on release? Come and listen to our exciting specialist speakers to find out more at our free Prison Hope event.

Peter Holloway, CEO Prison Fellowship England and Wales

Imam Abdul Dayan, Managing Chaplain at HMYOI Aylesbury

Revd Bob Wilson, Free Churches Faith Advisor to HMPPS

Peter Jones, Global Alpha for Prisons

David Portway, Aldates for Community Transformation (ACT)

Ex-offenders

Information stalls to promote volunteering include Prison Alpha; Prison Fellowship; Prison Visiting; New Leaf Project (mentoring)

Date and Time

Location

Aylesbury

Vineyard Church

Gatehouse Close

https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/prison-hope-tickets-35880953899http://www.russellwebster.com/hmip-dameglenys-sep17/

No comments:

Post a Comment

comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.