Big rise in deaths of offenders on probation

More people under probation supervision are dying.

A very sad post today, summarising information from a Ministry of Justice statistics bulletin: Deaths of Offenders in the Community 2016/17 published just over a week ago (26 October 2017).

Before looking at the figures which cover people under supervision by the probation service (both the National Probation Service and 21 Community Rehabilitation Companies) on a community order, suspended sentence order or on post-release licence, it is important to clarify a couple of things.

While probation services should certainly be encouraging the offenders they supervise to address health and wellbeing issues (particularly substance misuse and mental health concerns), they do not hold prime responsibility for the healthcare of the people they supervise and their accountability cannot be considered the same as it is for prisons who have a duty of care to people in custody.

This statement does not of course suggest that the deaths of offenders in the community are in any way less sad, or distressing for their families and friends, than those who die in prison. The two Community Rehabilitation Companies — Humberside, Lincolnshire and North Yorkshire & Norfolk and Suffolk — should be ashamed of their failure to submit returns about the number of people who died whilst under their supervision.

Main findings

The MoJ summarises the main findings of this statistical bulletin:

Thirteen of the offenders who died last year, did so while residing at a probation hostel (approved premises).

Thirteen of the offenders who died last year, did so while residing at a probation hostel (approved premises).

Post-release supervision

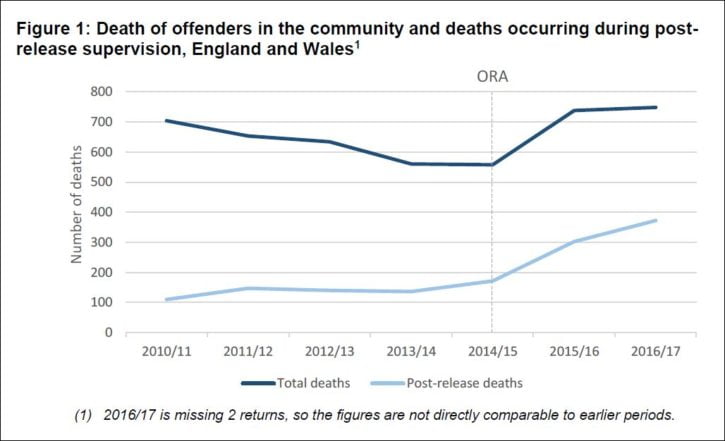

There were 748 deaths of offenders in the community in 2016/17, the highest in the time series despite missing information from two Community Rehabilitation Companies (CRCs). This is an increase of 7% (47 deaths) from 701 deaths in the previous year, after adjusting 2015/16 figures to account for the two missing data returns.

The increase in deaths in the community is due to the rise in number of offenders who died under post-release supervision, while deaths of other offenders have been falling. There was an increase of 82 deaths (28%) during post-release supervision compared to 2015/16.

The proportion of deaths in the community that occurred during post-release supervision has increased from 16% in 2010/11 to 50% in 2016/17. This is less surprising since the introduction of the Offender Rehabilitation Act (ORA) on 1 February 2015 led to a large increase in the number of offenders on post-release supervision. However, this does not explain the substantial increase in deaths amongst released prisoners in the last year.

Cause of death

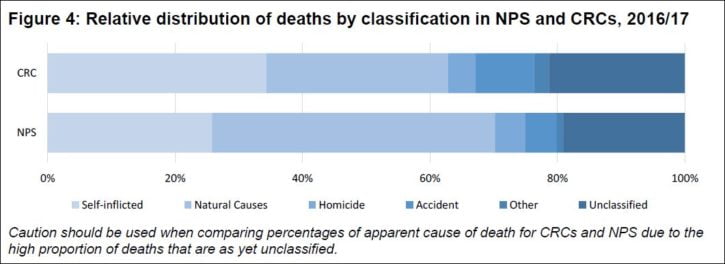

There were 258 natural-cause deaths in 2016/17, a 10% increase when compared with adjusted figures for 2015/16. Deaths due to natural causes accounted for around a third of all deaths in the community across the time series, although natural-cause deaths accounted for a higher proportion of all deaths of offenders supervised by NPS (44% in 2016/17) compared to CRCs (29% in 2016/17).

This difference may be explained partly by the age of offenders at the time of their death. For 2016/17, around 39% of offenders supervised by NPS were aged 50 or over when they died. Offenders in this age group are more likely to die of natural causes than any other reason.

In contrast, only 20% of offenders supervised by the CRCs were aged 50 or over when they died. There were 233 self-inflicted deaths in 2016/17, a decrease of 9% from 2015/16 and this accounted for 31% of all deaths.

In 2016/17, the proportion of self-inflicted deaths in the NPS was lower than the proportion of deaths due to natural causes. The opposite is true of the CRCs, where self-inflicted deaths accounted for a higher proportion of deaths than natural causes. This is only partly explained by the different age distributions of the supervised offenders. When comparing on a like-for-like basis, CRCs had a drop in the number of self-inflicted deaths compared to the previous year, whereas the NPS saw an increase.

There were 33 apparent homicides in 2016/17, 13 in NPS and 20 in CRCs. While this is the highest in the time series, it accounted for only 4% of all deaths, and is broadly consistent with previous years.

There were 33 apparent homicides in 2016/17, 13 in NPS and 20 in CRCs. While this is the highest in the time series, it accounted for only 4% of all deaths, and is broadly consistent with previous years.

Gender

In 2016/17, 40% of male and 19% of female offenders who died in the community were under the supervision of the NPS. There were 649 male deaths, accounting for 87% of all deaths, with 36% due to natural causes and 30% for for self-inflicted. This is in contrast to females where the main cause of death was self-inflicted (41%) and natural causes accounted for 25%. At the time of death, 29% of males were aged 50 or over compared to 17% for females. This age group is more likely to die of natural causes, which partly explains

the higher proportion of natural-cause deaths amongst males.

For males, 2015/16 was the only year in the time series to have higher numbers of self-inflicted deaths than natural causes. In both of the last two years, females have recorded more self-inflicted deaths than those due to natural causes.

the higher proportion of natural-cause deaths amongst males.

Conclusion

The fact that the report makes for sad reading is inevitable given its subject. However, there are real concerns to be raised around the increase in the number of deaths and the sad but compelling fact that more offenders supervised by CRCs will kill themselves than will die of natural causes.

We can only guess at the impact that the changes in the probation system brought in under the government’s Transforming Rehabilitation programme and the reduction in access to health services (particularly substance misuse and mental health treatment) which has accompanied the cuts in public funding over the last nine years, have contributed to these figures.

Public & Private Probation under-performing in West Mercia

By Russell Webster on Nov 09, 2017 05:47 am

Improvement needed

Today’s (9 November 2017) probation inspectors’ report on West Mercia adds to the litany of under-performing probation areas with both the public National Probation Service and private Community Rehabilitation Company found to require improvement.

Interestingly, despite meeting its national performance targets, the CRC was assessed as poor in key areas of work, including protecting potential victims from the risk posed by people under supervision. This work required improvement, particularly, in cases of domestic abuse and those involving the safeguarding of children.

NPS performance in the West Mercia division was judged to be variable

the NPS had experienced staff who managed offenders well and delivered good-quality interventions overall. However, … NPS staff were not using the wide range of interventions – programmes to support offenders – that were on offer from the CRC to the extent expected.

More detailed findings are set out below:

Findings — CRC

The main inspectors’ findings of the work of the CRC were:

- The quality of CRC work to protect those at risk of harm was poor. It required improvement, particularly in cases of domestic abuse and those involving the safeguarding of children.

- Initial assessment and sentence planning also required improvement.

- Some practitioners required more training and support to improve their practice in work to protect the public.

- The quality of case management was inconsistent. The CRC was not sufficiently effective in delivering enough interventions to reduce reoffending. A range of good-quality external services had been developed in partnership with the previous trust or the CRC, but their funding and use were being reduced for financial reasons.

- As part of its contract, the CRC had introduced a new initial assessment and sentence planning tool and set up multi-functional hubs from which the CRC and its partner organisations would provide services for offenders. Neither of these innovations had been successful in delivering additional benefits in quality or effectiveness, and the CRC had largely reverted to previous models of delivery that better fitted the operational context.

- Unpaid work was being delivered effectively.

- The quality of the CRC’s work to ensure sentences were fully implemented was poor.

- Offenders were not sufficiently involved in planning their order or licence, and contact was not sufficiently frequent or enforced. The number of absences deemed acceptable was too high. As a result, too few offenders completed the work that was required of them. The CRC needed to give more attention to increasing offender engagement.

The graphic below summarises performance on reducing reoffending by the NPS and CRC combined (no separate analysis of figures):

Findings — NPS

- The quality of the NPS’s work to manage risk of harm varied. Assessment and planning to manage risk of harm to others were sufficient. MAPPA was working well and contributed to keeping people safe but interventions needed to be more focused on protecting those at risk of harm.

- The NPS’s court liaison work required improvement. Pre-sentence reports were not of a consistently high enough standard, and court liaison work overall did not support the effective assessment of cases before allocation.

- The quality of assessment and planning was sufficient once cases had been allocated, but progress was not reviewed adequately.

- Overall, the NPS’s work to make sure offenders abided by their sentence was good. Individuals were fully involved in planning their order or licence. The NPS took factors relating to diversity into account.

- We found that the number of appointments offered was sufficient for offenders’ needs. As a result, the NPS delivered the legal requirements of orders and licences well.

Findings — Co-ordination between NPS and CRC

Working relationships between the CRC and the NPS were good overall:

- The variable quality of the NPS’s court work led to unnecessary pressures on the CRC. The NPS did not assess cases well enough before allocating them. The CRC was often given adequate information which contributed to the poor quality of the CRC’s initial assessments and plans.

- Court liaison work had not reversed the under-use by sentencers of the CRC’s accredited programmes to address domestic abuse, drink driving, and thinking skills.

- The CRC and NPS were working well together where necessary to enforce court orders and licences. The NPS was introducing a centralised process for enforcement across West Mercia.

- When cases were returned to court because of a breach, however, court listing arrangements resulted in considerable delays in hearing enforcement applications, with waits of up to six weeks at magistrates’ courts and up to three months at the Crown Court. This was undermining sentencers’ confidence in probation services.

Conclusions

Chief Inspector Dame Glenys Stacey uses this report to raise three more general issues. The first is that CRCs do not receive sufficient funding to do a good job. The second is that the HMPPS contractual targets are a poor indicator of good quality work:

The organisation was being driven by performance targets, as one might expect, and there was a strong central drive to discern how to meet targets and then do so. Managers and practitioners both recognised that this had little to do with delivering positive outcomes for individual offenders. Success in managing performance targets was not matched by efforts to maintain and raise the quality of offender management and to achieve positive outcomes with offenders.

The final point is that offenders supervised by the NPS do not get the proper range of interventions required to address their needs and promote desistance:

NPS staff were not using the wide range of interventions – programmes to support offenders – that were on offer from the CRC to the extent expected. Offenders may be denied the best help as a result, and the interventions themselves will be less viable over time, if they are not used enough. This is not the first time we have found this situation, and I urge the NPS to review the position nationally.

Probation Standards

The next time West Mercia is inspected, the inspectorate will rate them using new standards and assess them as Outstanding, Good, Requiring Improvement or Inadequate. If you’d like to have your say on what the new standards should look like, you have until 8 December to do so.

Click here to see my infographic summarising findings from the first thirteen inspections of the new public/private probation system.

The arrangements for interviewing clients in public library's are absolutely unacceptable

|

Dean isn’t here to take out a library book or use the free wifi. He is on probation for an offence that’s deemed him to be of “medium risk” to the public and has come here for his weekly meeting with his probation officer.

“I’m sorry, we don’t have any rooms available so we’ll have to have a chat over here,” says the probation officer when she arrives, gesturing to a table near teen fiction. Dean shuffles after her, looking tired and dishevelled. He is clearly conscious of the suspicious looks being cast in his direction.

The whole conversation between Dean and his probation officer can be overheard – it includes his fears of becoming homeless again, his difficult relationship with his family, and an update on how his course of methadone is going.

These are personal issues that you would expect to discuss in private. But with only one interview room between six probation officers, highly sensitive and potentially volatile conversations such as this are having to be played out in public.

Until last year, Weston-super-Mare’s probation team were able to meet offenders at their purpose-built facilities by the courts. But 15 months ago, its staff were moved into the town hall, where they share office space with the council’s housing team and the Avon and Somerset police. The aim is to bring services closer together in an attempt to reduce offending behaviour.

Now the six probation officers have to interview at least a dozen of the 25 people they typically see a day in public, due to alack of meeting rooms.

“This is the most untenable, dangerous situation I’ve witnessed,” says Julie Wright, a probation officer with 10 years’ experience in various English towns and cities, before moving to North Somerset. But she was so appalled by the service she was expected to deliver in the public library that she quit her new job after just two days.

“The staff are on their knees, it’s putting the public at risk, and the service users are being stigmatised and denied a proper chance to engage in rehabilitation,” she says.

In June 2014, 70% of probation work in England and Wales was outsourced to 21 community rehabilitation companies (CRCs) in England and Wales. Only the most dangerous offenders – those deemed “high risk” – are still supervised by the public sector, under the remit of a new National Probation Service (NPS). Critics of the controversial probation privatisation say what is happening in Weston-super-Mare is symptomatic of – and a grim indictment of – the poor service that has followed.

The arrangements for interviewing clients in a public library are absolutely unacceptable.

The arrangements for interviewing clients in a public library are absolutely unacceptable,” says Ian Lawrence, general secretary of Napo, which represents more than 8,000 staff working in probation and family courts in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The number of serious crimes such as murder and manslaughter committed by offenders under supervision in the community has risen by 25%since privatisation. In 2012-13, 409 serious further offence reviews were triggered, yet by 2016-17 this had increased to 517. The Ministry of Justice says comparisons are misleading, as it reformed the system so the numbers of offenders on probation are now significantly higher. “Our probation reforms have meant that around 40,000 offenders who previously would not have been supervised – because they had been in prison for less than 12 months - are now being monitored for the first time,” says a MoJ spokesman. “But we have been clear that we need probation to work better. We want more intensive rehabilitation to take place in the community, particularly to tackle offenders with substance misuse and mental health needs. And we want tough community sentences that are consistently and effectively enforced so they command the confidence of the courts and the public.

But it is not as if the MoJ were unaware of the potential problems. A leaked document in 2013 by senior officials warned that there was a more than 80% risk that the privatisation proposals introduced by the then justice secretary Chris Grayling, would lead to “an unacceptable drop in operational performance”. In Bristol, Gloucestershire, Somerset and Wiltshire, community probation services are run by Working Links – a global company delivering government welfare-to-work, criminal justice and learning and skills outsourced contracts. It also won the contract to run the CRC in Wales and covering Dorset, Devon and Cornwall.

In August, Working Links received a damning report from the probation inspectorate for its service in Gloucestershire. The quality and impact inspection found that “painful staffing reductions”, “unacceptable workloads” and facilities that were not fully functioning were putting the public at “more risk than necessary” and denying service users the chance to turn their lives around.

The Working Links service in North Somerset has yet to be inspected. But HM chief inspector of probation, Dame Glenys Stacey, said of Gloucestershire: “This CRC’s work is so far below par that its owner and government need to work together urgently to improve matters, so that those under supervision and the general public receive the service they rightly expect, and the staff that remain can do the job they so wish to do.”

Conducting interviews in public is particularly detrimental for vulnerable women, says another ex-staff member, speaking on condition of anonymity. She describes a situation with a female offender having to be interviewed within earshot of her ex-partner – a perpetrator of domestic violence. “He deliberately sat at the nearby computer station in order to intimidate her.”

Sometimes unsuspecting members of the public will sit on the same table and settle down with a book, she adds. When I was there a man interrupted an interview to ask about the wifi password, mistaking the probation worker for a librarian.

“Situations like that happen all the time and it undermines what we are trying to do – we can’t challenge people about their offending or go into any meaningful detail,” the ex-staff member explains. “A lot of the people we work with are very traumatised, vulnerable people who are a risk to themselves as much as they are to others.” Welfare changes, benefit sanctions, a huge shortage of affordable housing and cuts to support services have limited the help that probation offices can signpost for ex-offenders, she adds.

“We anticipate that the rollout of universal credit will make life much tougher for our client group as many of them survive on limited benefits or zero-hour contracts.”

In a town where 40% of people live in poverty, she says her clients arrive in increasingly more desperate states and many are sofa surfing. “There is only housing association accommodation that people can bid for, some voluntary sector social housing such as accommodation for people with mental health problems and the private rented sector. But very few private rented sector landlords will rent to people on benefits.”

Emotions can run high – sometimes people become angry and abusive and the public library setting doesn’t help to de-escalate things, says the ex-staff member.

Probation colleagues in Bristol are also having to compromise on privacy. The CRC’s building better relationships group, run for perpetrators of domestic violence, has been moved from purpose-built offices to a shared space run as a community enterprise. “The group is held behind a door but it has no security. Reception staff is limited and anyone could walk into the group room,” sources close to Bristol CRC say.

“There have been incidents, including a chair being thrown through a door. There is a creche on site and vulnerable women who attend the centre for various community events. The programme’s team is under-staffed, so often the group is run by two women on their own in the evening.”

Napo says senior management consistently blame staff for their failings, saying that the problems are due to maternity leave, sickness and staff shortages. Says Lawrence: “All of this should have been factored in before they made nearly 40% of their staff redundant. We have little confidence that they will make a recovery from this or that they have an adequate plan to address these issues.”

Asked about concerns raised in Weston-super-Mare and Bristol, a spokesman for the Bristol, Gloucestershire, Somerset and Wiltshire CRC says: “Weston Town Hall is part of our wide network of community hubs, designed to bring services closer together to reduce reoffending behaviours. We share this venue with Avon and Somerset police and North Somerset council’s housing team – two of our main partners delivering important services affecting our service users.

“At all times we aim to deliver a safe service, working in an environment enabling us to build up trust and relationships with the people we support. We are talking with the council about the facilities and are exploring options to ensure we continue to deliver safe services that deliver results for our service users and the wider community.”

A spokeswoman for North Somerset council says: “Following concerns, a new health and safety assessment has been undertaken to review existing arrangements and the CRC are currently looking for alternative locations to see some of their service users. The Town Hall reception and library area has a security officer present during opening hours.”

failing service after part-privatisation introduced by Chris Graylinghttps://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/dec/06/liz-truss-calls-rapid-completion-probation-privatisation-review

The local Conservative MP, John Penrose, who had been informed about the concerns raised by probation staff says: “I’m very pleased Working Links accept that they need to find alternative, better accommodation and are exploring options with the council.”

I speak to Dean outside after his interview and ask whether he would have preferred to be in a private room. “Yeah, that might have been nice,” he says. “A bit of privacy, a bit of quiet and the chance to have a proper chat – I don’t really have that in my life, but it’s just one of those things,” he says with a shrug. He doesn’t seem to expect any better.

Later I tell the ex-staff member about our exchange. “A lot of our service users have been disadvantaged all their lives and have come to expect very little from the world,” she says. “It’s very sad – they deserve a proper chance to turn their lives around.”

A Ministry of Justice spokesman says: “We are looking very closely at these issues as more needs to be done. Public protection is our top priority and it is vital that we have in place probation services that not only keep people safe, but help offenders turn away from a life of crime by ensuring they have the correct levels of supervision and support.”

http://www.russellwebster.com/offender-deaths2017/

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/nov/01/privatised-probation-services-libraries-ex-offenders

No comments:

Post a Comment

comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.