Meet The Women Fighting For Prisoners With No Release Date

Almost 4,000 prisoners in England and Wales have indeterminate sentences and don’t know when, or if, they will be released. BuzzFeed News speaks to three women who are fighting for their loved ones to come home.

Martin Stephens was imprisoned almost 13 years ago, after he pleaded guilty to possession of an air rifle in public, at the scene of a robbery at a branch of Tesco in north London. No shots were fired.

The men who were charged with the robbery and theft of £580 served less than a year in prison. But Stephens, who was charged with only possession, is still inside. Now 51, he has no set release date, and no immediate prospect of being given one.

Why is he still in jail? Because Stephens was given a sentence of imprisonment for public protection (IPP). He is detained indefinitely unless or until a parole board is satisfied he no longer poses a threat to society.

Stephens’ tariff – the minimum length of time IPP prisoners must serve before they can be released – was one year and 47 days. He has served eight and a half times that. Given that prisoners are typically released after half their sentence, if their behaviour is good, Stephens has served the equivalent of a 26-year sentence.

He had already served 15 years for robbery in an earlier, unrelated incident. Almost half his life has been spent behind bars.

Jacquie Fahy, Stephens’ partner of four years, who is campaigning for his release, says it’s clear he poses no public threat. “The gun wasn’t used, he didn’t make a threat to kill – obviously the security guard was frightened. But it was a petty crime and he didn’t even do [the robbery], they only charged with him with the firearm, not for the robbery,” says Fahy. Yet after repeated parole hearings – which happen only every year or two – Stephens is still in prison.

IPP was brought in by the 2005 Labour government as a way to extend the sentences of some offenders guilty of sexual and violent crimes, and then abolished in 2012 by the Coalition. The chief inspector of prisons, Peter Clarke, last year called the sentences “completely unjust”. But some 3,800 prisoners who were given IPP sentences before 2012 are still stuck with them.

Some 87% of these prisoners have served more than their original tariff and 42% are more than five years over.

In some cases, such as that of Stephens, they could have spent less time in prison if they had been given a determinate sentence for a more severe offence.

“It’s a terrible thing to say, but he should have shot [someone] because he might have got out by now,” says Fahy of Stephens’ actions at that Tesco years ago. “And how can you go around saying things like that?”

BuzzFeed News spoke to Fahy and two other women who have dedicated their lives to getting a firm release date for IPP prisoners. Each of them says the men they are supporting are losing the will to live in the face of endless uncertainty.

Each says they are struggling against an overworked, complicated, and bureaucratic system in which it can take months or even years to secure a parole hearing.

Amid the crisis of violence, understaffing, and drug use plaguing Britain’s jails, these men are held years after they should have been released. If they do get out, they will spend at least 10 years on licence, meaning they can be put back in jail for the smallest of infringements.

Fahy says that she has campaigned so hard on this that Home Office staff know her by name. She has received written replies from a range of politicians who are sympathetic to her position and met with Boris Johnson in his tenure as London mayor to discuss the case. Johnson told her he owned guns himself and had never heard of a case like this. She says Johnson told her, “He would have been better off doing a murder, in terms of the time he’s been in there.”

All three women accept that their loved ones did wrong and owed a debt to society. But they now live with the stress of not knowing when, or even if, these men will be released.

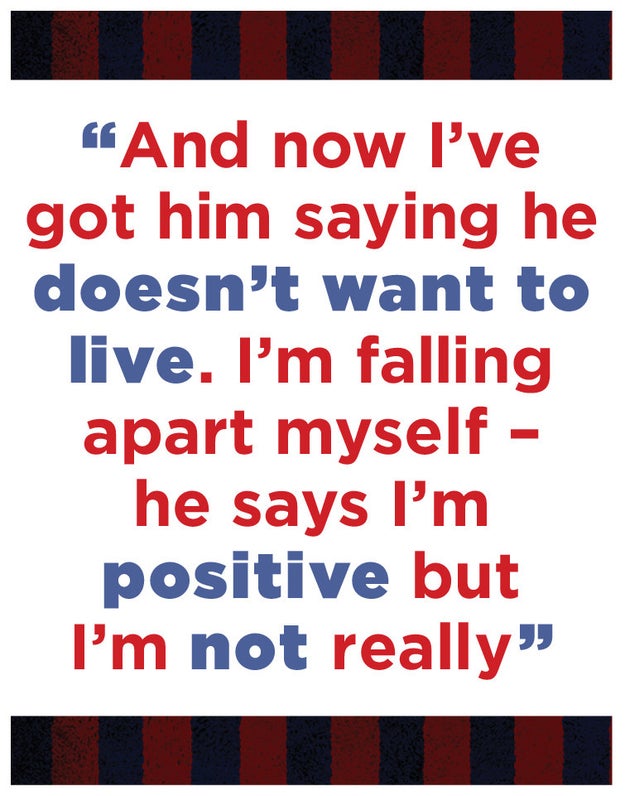

“I’m sorry, it’s just really upsetting. People don’t know how hard it is,” says Fahy. “They’re not getting back to him and he thinks he will never get out. He doesn’t want to live. I’m out here trying to sort things out and getting nowhere.

“And now I’ve got him saying he doesn’t want to live. I’m falling apart myself – he says I’m positive but I’m not really.

“If you murder someone or you’re in there on a sexual assault, at least they get out, which you hear about in the news all the time.”

Nick Hardwick, the head of the parole board in England and Wales, replied to Fahy’s desperate pleas in a letter to say his board took the matter seriously. He said in November last year that the board was seeing 40 prisoners a week and releasing 40% of them; he added that the IPP population had dropped from 6,000 in 2012 to just under 4,000 in late 2016.

Hardwick previously said that 1,500 IPP prisoners would be released by 2020, adding that others should not be released because of the threat they still posed.

Clarke, the chief inspector of prisons, last year said progress in releasing the prisoners had been “painfully slow”.

The problem is partly one of resources – the backlog was so great that 100 new parole board members were hired last year – but also policy: The board will only release prisoners who fulfil its criteria for parole, which aren’t made public. A Ministry of Justice briefing paper says that evidence is taken from professional witnesses, such as psychologists.

Government intervention could change this: Former justice secretary Michael Gove has urged the current secretary, Liz Truss, to use her powers of executive clemency to release the 500 IPP prisoners who had served longer than a normal sentence for the same offence.

The families BuzzFeed News spoke to argue that the reality is that petty infringements and a focus on prisoners completing spurious courses contribute to parole being denied.

IPP prisoners often have to complete a series of “offender behaviour courses” to prove their eligibility for release, with names like “Think First and Enhanced Thinking Skills” and “Controlling Anger and Learning To Manage It”. The courses are not compulsory, but failing to attend could affect the risk assessment that parole board decisions are based on.

“At Warren Hill [prison] where he is now, he turns up at these courses and they ask him why he’s there, that he doesn’t need to do it,” says Fahy. “Then he gets upset.”

Fahy told BuzzFeed News course leaders are just as bemused as Stephens about why his attendance is necessary.

Stephens has also had his chances hurt by bad behaviour, some of which was the result of errors by the prison system, says Fahy. He became angry after receiving the drug test result of another prisoner and “told them what he thought of them” and kicked a fence.

The mix-up was accidental, but the damage had been done. The outburst was noted by the parole board. On another occasion, he was denied category D status – effectively “open” prison conditions, where community releases can be arranged – due to what Fahy calls an administrative error.

“People on IPP won’t reoffend [on the outside] but they will in prison, 100%,” she says. “Because if they speak their mind it’s classed as aggression. And then you can’t get out because they count that against you or send you on another course.”

The maximum period between parole hearings is two years and typically they are given every 15 or 16 months. In some cases this period can be shortened if there is evidence the prisoner is making good progress.

Parole decisions can’t be appealed but prisoners can launch a judicial review – but the bar for success on review is very high and all it would achieve is another hearing.

And while the men remain in prison, they experience the difficult conditions of violence, understaffing, and drug use plaguing Britain’s jails.

“Someone died in the cell next to his yesterday. They left them all day in the cell, they had a heart attack. He [Stephens] got all upset about it and was in mental health [treatment] today. He fell out with the screw over it,” says Fahy.

“But how can you physically leave someone in there all day? It would make me go off. He started saying that if they can leave a dead person in there from 8am to about 6pm, if you can’t even move a dead body out of prison, what chance is there of getting out alive?

Susie is obsessed. She researches the law surrounding IPP sentences on a daily basis and stays in touch with a solicitor.

“My brain doesn’t stop going the whole time. If I’m not thinking about him, I’m thinking about ways to help him. And not just him but everybody [on IPP sentences],” she says.

“I feel like I hold the key and his freedom is on my shoulders. I feel like I have the key and I can’t find the lock. It’s somewhere but I don’t know where. But I have to find it.”

Her partner – she asked that he remain anonymous and that BuzzFeed News use only her middle name, for fear of affecting his parole chances – is 31 and has been inside for 11 years. His tariff was two and a half years, for aggravated burglary, yet he spent his entire twenties inside.

The hardest thing for her is how despondent he can be.

“They’ll keep him in there and put him on another course, all of which institutionalises him even more. This guy’s tortured, he’s being mentally tortured. He doesn’t have any hope. His solicitor says he hasn’t come across anyone as hopeless,” she says.

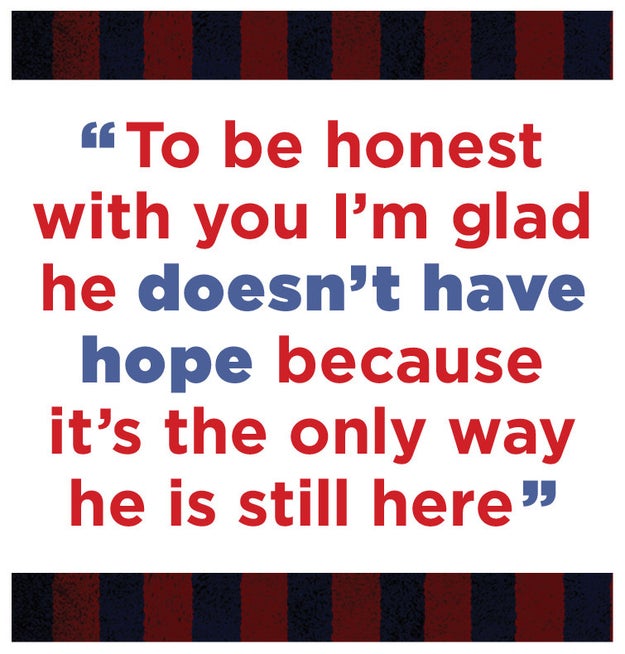

“To be honest with you I’m glad he doesn’t have hope because it’s the only way he is still here. If he hoped for a future, if he prayed for the life he had, if he hoped every time that parole came back and he got knocked back for some stupid nicking [being disciplined for an infringement] he got the year before for something ridiculous, he would be on the road to self-destruction.

“The maximum, very maximum, sentence he could have served for the crime he did was nine years without IPP – and that would have been four and a half custodial and the rest served [in the community] through probation and on a tag. He would have been out and able to move on with his life about a year and a half ago.”

He handed himself into the police and pleaded guilty, but – partly because of a previous offence he committed as an 18-year-old – he was given an IPP.

He was due to have a parole hearing in August 2016, but it was delayed. As Susie puts it, “You’re looking at a six-month sentence just through being on parole delay.”

“I go and see him once a week and I don’t think there’s 30 seconds that goes by where we don’t look at each other and think, ‘One day,’” she says. “And every time I leave I think, ‘One day.’

“I’m jealous of people with husbands inside who just have to wait until 2018. They’re lucky. They don’t have to contact the solicitor every five minutes asking, ‘Will this help? Will this help?’

“I just feel like he’s been screwed over so much, I can’t just leave him and do nothing. But I’ve chosen this.”

Jennifer O’Gorman is campaigning on behalf of Matthew Thomas, 55, who was given a three-year tariff on an IPP sentence in 2010 for attempted grievous bodily harm with intent, in a road-rage incident – a row over a parking space.

Thomas isn’t O’Gorman’s partner but her best friend. She was friends with his wife before she died.

“The judge said that if he was given a determinate sentence he would have given him six years. He’s now done seven and he’s still waiting for review,” she says.

“He was supposed to have a review [hearing] last year and he wasn’t even informed about it; it was just done on paper instead, and it was refused.

“He’s had a lot of misfortune. He went in in 2009 around December, and the following July his wife died of cancer. He had a heart attack the following year, his mother died the year after that. He’s developed lupus since being in prison – a lot of that is stress-related.”

For O’Gorman, the injustice of the situation is almost too much to take. “The fact [is] that the IPP sentence was abolished in 2012, so why would you just leave people languishing in prison with no hope?” she asks.

“But it’s the sheer backlog of it at the moment. Everyone is saying it’s wrong and inhumane but how do you cope with the paperwork?

“This is somebody’s life. A lot of people don’t care, it’s like ‘he’s not on the list [for a parole hearing], just wait for the next one.’ He’s vulnerable in prison because of his health.”

As with many other IPP prisoners, Thomas had previous offences and had been to prison before. And O’Gorman admits that what he did was wrong, but she argues that his debt to society is now paid.

“Obviously, you did the crime, you serve the time. But surely you’ve paid your debt. In Matthew’s case it doesn’t matter what he did in the past. The man he had a fight with wasn’t psychologically damaged or hospitalised.

“He’s done seven years – that’s equivalent to a 14-year sentence for an altercation that any of us could get into.

“Every time I go and see him you feel like you don’t want to leave him there. He’s surrounded by young men who are in and out, in and out and fighting all the time. He’s described it to me like being in a minefield that can go off at any time.

“How do you have hope when you don’t have an end date? That’s the crux of it. He does all this good in prison, he’s a wing rep, he’s an older prisoner rep, he’s a medical prisoner rep, he’s helping people filling in forms who can’t write English, he’s doing victim awareness and talking to people about restorative justice. He’s not a silly man, he’s a very intelligent man. He’s doing all this stuff, but all he wants to do is come home.”

O’Gorman points out that even if Thomas is released, that won’t be the end of it. IPP prisoners are typically released on licence, meaning they are bound by a strict set of rules and close monitoring in the community – any infringement could send them back to jail. For IPP prisoners this arrangement lasts for at least 10 years – unusually long.

“He does think it’s an unfair situation,” she says. “Especially when you consider that when he comes home it’s not really freedom to be on licence. Any misdemeanour, any little thing that causes you to be late for a [probation] meeting, and you’re gone.”

O’Gorman points out that because IPP sentences were given to violent and sexual offenders as well as those in jail for petty crimes, that means there isn’t much sympathy over the issue.

“I think the fact they’ve grouped it all together, with violent crime and sexual crime, that’s made it harder – when it’s paedophiles, people don’t want to know.”

She raises the prospect of a legal challenge from the IPP prisoners “for the years they have lost”, but then adds: “Matthew would say he doesn’t want the money, he just wants his freedom.”

Frances Crook, CEO of the Howard League for Penal Reform, told BuzzFeed News: “Open-ended sentences are grossly unfair as they remove hope and clarity.

“Whilst efforts are being made to move people through the prison system more quickly, the problem looming is the fact they will all be subjected to licence for life. People are already being recalled to prison for petty reasons.”

The Howard League says it is working with David Blunkett, the minister who introduced the sentences, to abolish the life licence and replace it with a fixed term of community-based observation and support on release.

The Ministry of Justice said in a statement: “We are working hard to reduce the backlog of cases involving IPP prisoners. We have set up a new unit within the Ministry of Justice to tackle this issue and are working with the Parole Board to improve the efficiency of the process.”

For the families of IPP prisoners, the wait goes on.

“I do believe that people who do something wrong should pay the price,” says O’Gorman, “but we all need an end date, we all need a light at the end of the tunnel.”

Katherine - thanks for your help posted on Jan. 18, 2017, at 5:01 p.m. https://www.buzzfeed.com/patricksmith/meet-the-women-fighting-for-prisoners-with-no-release-date?utm_term=.ka9ym2MXpk

Katherine - thanks for your help posted on Jan. 18, 2017, at 5:01 p.m. https://www.buzzfeed.com/patricksmith/meet-the-women-fighting-for-prisoners-with-no-release-date?utm_term=.ka9ym2MXpk

Contact Patrick Smith at patrick.smith@buzzfeed.com.

Got a confidential tip? Submit it here.

More:Full scale public row on the outside. https://www.buzzfeed.com/patricksmith/prison-guards-reveal-how-bad-the-safety-crisis-in-uk-jails?utm_term=.pf1bGgnKX#.noVk7Drgl

https://www.buzzfeed.com/patricksmith/prison-crisis-deepens-as-inmate-suicides-reach-epidemic-leve?utm_term=.ugeyBxqQz#.tb1Ml0J6G

https://www.buzzfeed.com/patricksmith/prison-diaries?utm_term=.wtVxarkEV#.auVvD5B0V

https://www.buzzfeed.com/patricksmith/prison-crisis-deepens-as-inmate-suicides-reach-epidemic-leve?utm_term=.ugeyBxqQz#.tb1Ml0J6G

https://www.buzzfeed.com/patricksmith/prison-diaries?utm_term=.wtVxarkEV#.auVvD5B0V

BBC Radio are looking to speak to people whose family or friends are serving an IPP sentence

Hi Katherine, I work for BBC Radio Gloucestershire. I'm looking to speak to people whose family or friends are serving an IPP sentence. Ideally people who live in Gloucestershire or the south west. Thanks

Email me : Katherine gleeson@aol.com

No comments:

Post a Comment

comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.