10 Dec 2020

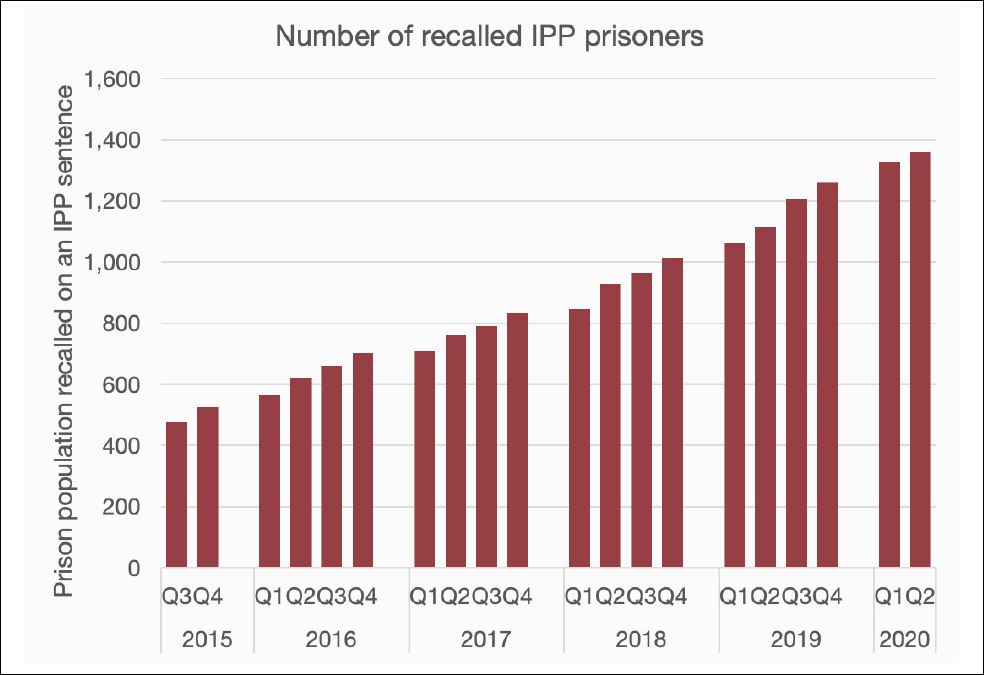

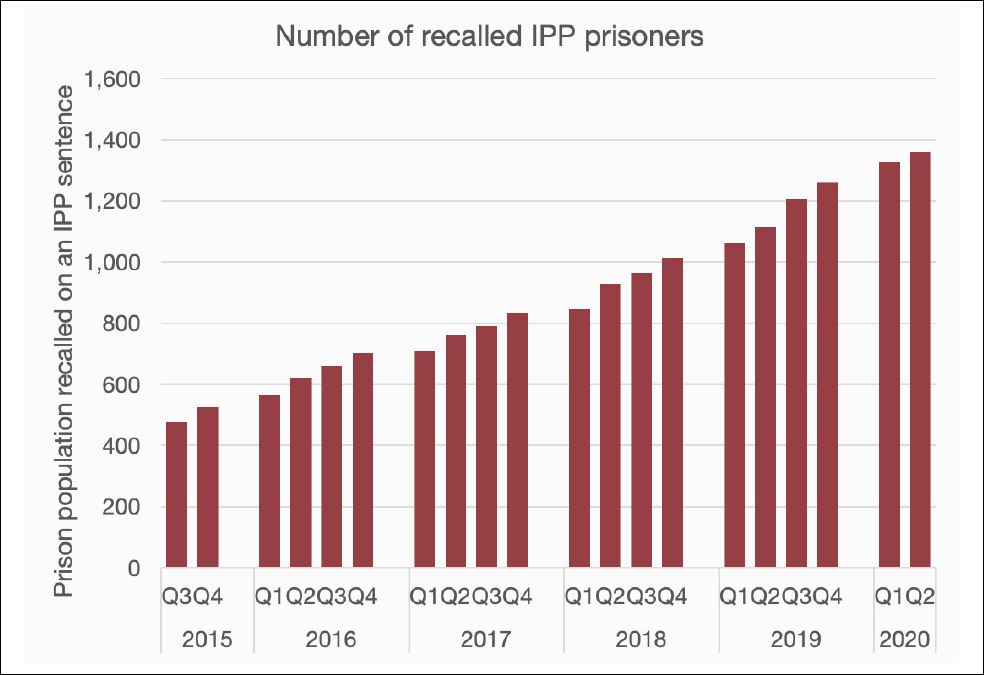

As a new report by the Prison Reform Trust makes clear, “the IPP problem” hasn’t gone anywhere. Instead, the indefinite licence means that numbers may remain the same or even increase in the immediate future. While the last five years have witnessed a fall in never-released IPP prisoners from 4,431 to 1,895, the numbers of those recalled to prison has skyrocketed by 184%, from 477 to 1,357.

The consequences are often catastrophic. At the end of November, it was reported that the Ministry of Justice had paid damages to the family of a man who had taken his own life at the Mount prison in Hertfordshire in 2015, having served two years over his four-year minimum tariff for stealing a car and injuring its owner. Tommy Nicol had described himself as living with the “psychological torture of a person who is doing 99 years”, just one of a number of handwritten complaints he’d filed during his sentence. Nicol’s case was not an anomaly: self-harming rates among IPP prisoners are 70% higher than among the general prison population.

As a new report by the Prison Reform Trust makes clear, “the IPP problem” hasn’t gone anywhere. Instead, the indefinite licence means that numbers may remain the same or even increase in the immediate future. While the last five years have witnessed a fall in never-released IPP prisoners from 4,431 to 1,895, the numbers of those recalled to prison has skyrocketed by 184%, from 477 to 1,357.

The consequences are often catastrophic. At the end of November, it was reported that the Ministry of Justice had paid damages to the family of a man who had taken his own life at the Mount prison in Hertfordshire in 2015, having served two years over his four-year minimum tariff for stealing a car and injuring its owner. Tommy Nicol had described himself as living with the “psychological torture of a person who is doing 99 years”, just one of a number of handwritten complaints he’d filed during his sentence. Nicol’s case was not an anomaly: self-harming rates among IPP prisoners are 70% higher than among the general prison population.

Nicol had tried his best to fight for release, but it wasn’t enough. Like so many others, he had repeatedly been denied access to the rehabilitative courses and mental health treatment that form the crucial evidence for any parole board’s decision. Prison damages people. It is a violent, stressful world. Withholding the support someone has asked for, which is crucial to their chances of even partial freedom, is wilful cruelty. And if it flourished before, then conditions are even less propitious now. During the pandemic, almost all rehabilitation support has stopped, creating a backlog of parole hearings, with IPP prisoners again pushed to the bottom of the pile.

That the criminal justice system is in disarray is hardly news. Multiple governments have calculated that there is little to be gained by treating prisoners as anything other than politically expendable. But surely no functioning society can tolerate a situation where thousands of people are incarcerated having already paid back their debt to society, multiple times over? In 2019, the Prison Reform Trust reported that England and Wales have more people currently serving indeterminate sentences than Germany, Russia, Poland the Netherlands, Italy and Scandinavia combined. Despite its supposed abolishment, the continued existence of IPP isn’t just an embarrassment, but a national disgrace.

Government and prison Failings

in

-Administration

-Duty of care

-Accountability

-Denied access to rehabilitation in mutable ways repeatedly since there sentence

-Heavy death tole of IPP prisoners kept out of sight of the media and public

-Government failed to deal with crises causing mental health of those sentence to a IPP sentence.

-Repeatedly been denied access to parole and hearings.

-Men and woman never given a date of release.This effected the right for there children not knowing when they can see there children or parent again.

-Those with autism and neurological disability's denied access to reasonable adjustments putting them at risk. Pentonville prison condemned by inspector for failing to let inmates in wheelchairs go outside | Evening Standard

-prisoners health and complaints dismissed time after time.

-Independent investigation not yet carried out?

IPP prisoners are less a dangerous then the rest of the prison population by definition being a snap shot but yet the sentence was over kill.

99 years for stealing a phone Blunkett admitted he got it wrong and a violation of human rights !

Kiya Smith , Stole a phone and received 99 years sentence 'My son stole a phone aged 17. Soon he'll have spent 10 years in jail for it' - Wales Online

Jason Dunn, Stole a phone and received 99 years sentence 'Lost' prisoner STILL locked up 15 years after two year jail sentence for stealing mobile phone - Leicestershire Live (leicestermercury.co.uk)

Cruel and harmful IPP sentencing regime in England and Wales called 'deeply harmful' | UK criminal justice | The Guardian

Crudely thought out and over-zealously implemented, it marked the worst of New Labour’s “tough on crime” machismo. IPP is essentially an indeterminate sentence: those convicted are given a minimum jail tariff (the term that is considered appropriate for their actual wrongdoing) but no maximum. After being released they are placed on indefinite licence (when you serve a sentence in the community), which is subject to being recalled to prison. Applications to terminate this licence can only be made after 10 years.

At first, the justification was that indefinite sentences would keep the most dangerous violent and sexual offenders off the streets for as long as they remained a threat to the public. The reality has proved to be one of the most egregious criminal justice scandals in modern British history.

While the government of the day had expected the prison population to increase by about 900 people as a consequence of IPP sentences, at its peak the true figure was many times this number, due to the 8,711 sentences passed between 2005 and 2013. The definition of who exactly constituted the “most dangerous” criminals proved elastic. Many, such as Lloyd, had been condemned to a sentence without a release date (with the prospect of a 99-year probation to follow) for relatively minor crimes, including petty theft, affray and criminal damage worth less than £20.

DECEMBER 5, 2020

New research by the Prison Reform Trust reveals the mental anguish faced by the growing number of people serving sentences of Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPPs) recalled to prison for breach of their licensce conditions – a population which has nearly tripled in the past five years.

One recalled IPP prisoner interviewed for the report despaired of having “no life, no freedom, no future” under the discredited sentence, which was abolished in 2012.

Describing in graphic detail the impact of the IPP and the cycle of release and recall on his own mental health and wellbeing, the prisoner says: “So long as I’m under IPP I have no life, no freedom, no future. I fear IPP will force me to commit suicide. I have lost all trust and hope in this justice system...Each day I feel more and more fear and dismay and I am starting to dislike life...I have to suffer in prison in silence. Accept it or suicide. That’s my only options left.”

The report, entitled No life, no freedom, no future after this quote, explores the experiences of people recalled whilst serving IPP sentences. Its findings are based on new data provided by HM Prison and Probation Service on recalls and re-releases of people serving IPPs; interviews with 31 recalled IPP prisoners; and interviews and focus groups with a range of criminal justice practitioners including probation, parole and prison lawyers.

The report’s analysis of the data demonstrates that the “IPP problem” is not diminishing over time. The indefinite nature of the IPP licence means that it is quite possible that the number of people on IPP sentences in prison remains the same or even increases for the foreseeable future. Over the past five years (from 30 September 2015 to 30 September 2020) the number of never-released IPP prisoners has fallen by 57 per cent from 4,431 to 1,895. However, in the same period, the number of recalled IPP prisoners has grown by 184 per cent from 477 to 1,357.

Writing in the foreword to the report, Lord Brown of Eaton-Under-Heywood, a Justice of the Supreme Court from 2009–2012, said: “We are in a shocking and shaming position and, unpropitious though the present time might appear to be, it is imperative that this compelling report now be widely read, digested and fully acted upon. Our reputation as a just nation demands that this IPP stain be at last eradicated.”

The report found that IPP prisoners’ life chances and mental health were both fundamentally damaged by the uniquely unjust sentence they are serving. Arrangements for their support in the community after release did not match the depth of the challenge they faced in rebuilding their lives outside prison. Risk management plans drawn up before release all too often turned out to be unrealistic or inadequately supported after release, leading to recall sometimes within a few weeks of leaving prison, and for some people on multiple occasions. The process of recall also generated strong perceptions of unfairness.

At its worst, the report found that the system:

- recalled people to indefinite custody for behaviour that appeared to fall well short of the tests set in official guidance

- defined needs (e.g. mental health) as risk factors

- ignored the impact of the unfairness of the sentence on wellbeing and behaviour

- could not provide the necessary support

- provided no purpose to time back in custody or a plan for re-release.

Not all IPP prisoners experienced all of these, but they were common enough to reveal a system in need of radical improvement.

The report warns that there must be fundamental changes to the way in which people serving IPP sentences are supported. Recommendations include a reduction in the length of time before which people are entitled to have their licence reviewed from 10 to five years, with a yearly review after that period. It also recommends changes to the recall test and process so that individuals on IPP licence are not at risk of far more severe punishment than their behaviour would otherwise justify.

As the injustice faced by people serving IPP continues, and seems set to increase, the report concludes that the abolition of the IPP sentence should be made to apply retrospectively. This would require a process of judge-led reviews of individual IPP cases; a phased programme of releases, with properly resourced preparation, and post release support plans for all those affected. All IPP prisoners should have a fixed date on which their liability to recall ends.

Peter Dawson, director of the Prison Reform Trust, said: “The problem of the IPP sentence is not going away. Ministers will say their priority is public protection, but that should mean making sure that all the effort that has gone into getting IPP prisoners safe to release is matched by a similar effort to help them succeed in the community. Recall to custody is a sign of failure, not success, and only makes the task of motivating someone to try again that much harder. The continued existence of the IPP sentence, and the worsening situation this report discloses, makes every political appeal to our great tradition of justice sound hypocritical. The problem is very far from being solved, and demands the urgent attention of both ministers and parliament.”

* Read No life, no freedom, no future here

Tommy Nicol: Family wins wrongful death over HMP Mount

Nicol's family had begun a landmark claim in the High Court, in which they argued that the lack of a maximum term led directly to his death and therefore the Human Rights Act 1998.

Number of recalled IPP prisoners in custody almost triples in five years

The government has agreed to pay compensation to the family of a prisoner who took his own life six years into an indefinite sentence.

Tommy Nicol, 37, died at Watford Hospital in September 2015, four days after he was found unresponsive in his cell at HMP The Mount, Hertfordshire.

At the time of his death, Nicol was two years past his minimum prison term.

The Ministry of Justice (MoJ) said: "Our sympathies remain with the family and friends of Mr Nicol."

Nicol was jailed at St Albans Crown Court in 2009 after injuring a mechanic while stealing a car from a garage.

He was jailed for a minimum of four years under the Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP) sentencing scheme, which has since been abolished.

What are IPPs?

- IPPs were introduced in 2003 and designed to ensure dangerous offenders remained locked up until they no longer posed a risk

- However, they were given to more offenders than originally expected, including those guilty of what critics described as "lower level" crimes

- IPPs were abolished in 2012 - but not for existing prisoners

Nicol's family had begun a landmark claim in the High Court, in which they argued that the lack of a maximum term led directly to his death and therefore the Human Rights Act 1998.

They said he had described his sentence as the "psychological torture of a person who is doing 99 years."

Six years into his sentence, Nicol was told by a parole board that his next review would be in 2017.

His family said that was a catalyst for a sharp deterioration in his mental health and he became suicidal.

"The last five years have been a long and painful journey," Nicol's sister, Donna Mooney, said.

"The settlement of our claim provides our family with some semblance of justice".

The amount paid to the family has not been disclosed.

In its statement, the MoJ added: "We have provided specialist suicide and self-harm training for over 25,000 staff [across the country] and have recruited 4,000 new prison officers since 2016, allowing us to provide dedicated support to each prisoner."

|

Losing trust and hopeI’m delighted to share the information in this post on new research into the experience of people on IPP sentences who have been recalled to prison. The research was conducted by Kimmett Edgar and Mia Harris of the Prison Reform Trust in partnership with myself. New (3 December 2020) research by the Prison Reform Trust reveals the mental anguish faced by the growing number of people serving sentences of Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPPs) recalled to prison for breach of their licence conditions – a population which has nearly tripled in the past five years. One recalled IPP prisoner interviewed for the report despaired of having “no life, no freedom, no future” under the discredited sentence, which was abolished in 2012. Describing in graphic detail the impact of the IPP and the cycle of release and recall on his own mental health and wellbeing, the prisoner says: “So long as I’m under IPP I have no life, no freedom, no future. I fear IPP will force me to commit suicide. I have lost all trust and hope in this justice system… Each day I feel more and more fear and dismay and I am starting to dislike life. . . . I have to suffer in prison in silence. Accept it or suicide. That’s my only options left.”

The report, entitled No life, no freedom, no future after this quote, explores the experiences of people recalled whilst serving IPP sentences. Its findings are based on new data provided by HM Prison and Probation Service on recalls and re-releases of people serving IPPs; interviews with 31 recalled IPP prisoners; and interviews and focus groups with a range of criminal justice practitioners including probation, parole and prison lawyers. The report’s analysis of the data demonstrates that the “IPP problem” is not diminishing over time. The indefinite nature of the IPP licence means that it is quite possible that the number of people on IPP sentences in prison remains the same or even increases for the foreseeable future. Over the past five years (from 30 September 2015 to 30 September 2020) the number of never-released IPP prisoners has fallen by 57% from 4,431 to 1,895. However, in the same period, the number of recalled IPP prisoners has grown by 184% from 477 to 1,357.  The report found that IPP prisoners’ life chances and mental health were both fundamentally damaged by the uniquely unjust sentence they are serving. Arrangements for their support in the community after release did not match the depth of the challenge they faced in rebuilding their lives outside prison. Risk management plans drawn up before release all too often turned out to be unrealistic or inadequately supported after release, leading to recall sometimes within a few weeks of leaving prison, and for some people on multiple occasions. The process of recall also generated strong perceptions of unfairness. At its worst, the report found that the system: - recalled people to indefinite custody for behaviour that appeared to fall well short of the tests set in official guidance;

- defined needs (e.g. mental health) as risk factors;

- ignored the impact of the unfairness of the sentence on wellbeing and behaviour;

- could not provide the necessary support; and

- provided no purpose to time back in custody or a plan for re-release.

Not all IPP prisoners experienced all of these, but they were common enough to reveal a system in need of radical improvement. The report warns that there must be fundamental changes to the way in which people serving IPP sentences are supported. Recommendations include a reduction in the length of time before which people are entitled to have their licence reviewed from 10 to five years, with a yearly review after that period. It also recommends changes to the recall test and process so that individuals on IPP licence are not at risk of far more severe punishment than their behaviour would otherwise justify. As the injustice faced by people serving IPP continues, and seems set to increase, the report concludes that the abolition of the IPP sentence should be made to apply retrospectively. This would require a process of judge-led reviews of individual IPP cases; a phased programme of releases, with properly resourced preparation, and post release support plans for all those affected. All IPP prisoners should have a fixed date on which their liability to recall ends. ConclusionThis was a profoundly affecting study to work on. I had known for many years how unjust the situation was for people serving an IPP. But, as is often the case, being confronted with individual stories which showed the ongoing traumatic impact of that experience for people on IPPs and their families really conveyed the impossible nature of their situation. The IPP sentence is a perfect example of Catch-22 where any decision can result in the opposite of what you want: Be honest about your fears and problems in prison and risk being considered unsafe to release.

Ask for help for a mental health problem in the community and you could be assessed as higher risk and be recalled to prison.

Enter into a new intimate relationship in the knowledge that an upset partner could make false accusations which would result in recall. It is hard to imagine how any of us could hold on to our sanity and self-belief in this situation. |

|

|

|

|

Parlement 4tyh Dec 2020

Lyn Brown Shadow

Minister (Justice)

To ask the Secretary

of State for Justice, with reference to Prison Population Projections

2020 to 2026, England and Wales,

published on 26 November 2020, Table 1.1, if he will make an assessment of the

implications for his policies of the projected rate of decrease in the

indeterminate sentenced prison population.

As the projections show, the indeterminate population is

forecast to decline over the next 6 years. This is largely due to a continuing

decline in the number of prisoners continuing to serve the sentence of

Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP).

We are committed to ensuring that all prisoners serving

indeterminate sentences, including those serving IPPs, have every opportunity

to progress towards safe release. HM

Prison and Probation Service are focused on reducing the risk and

thereby the successful rehabilitation of IPP prisoners via an action plan which

is taken forward jointly with the Parole

Board. This approach is working, with high numbers of unreleased IPP

prisoners achieving a release decision each year and we expect this to

continue.

As the projections show, the indeterminate population is

forecast to decline over the next 6 years. This is largely due to a continuing

decline in the number of prisoners continuing to serve the sentence of

Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP).

We are committed to ensuring that all prisoners serving

indeterminate sentences, including those serving IPPs, have every opportunity

to progress towards safe release. HM

Prison and Probation Service are focused on reducing the risk and

thereby the successful rehabilitation of IPP prisoners via an action plan which

is taken forward jointly with the Parole

Board. This approach is working, with high numbers of unreleased IPP

prisoners achieving a release decision each year and we expect this to

continue.

The Observer 6th Dec 2020

|

This is a guest post by Peter Dawson, Director of the Prison Reform Trust. Prison population to jump by 25%The most recent prison population projections attracted

little if any public attention, despite an estimate that close to

100,000 of our fellow citizens could be in prison by 2026. This was

quickly followed by the Chancellor’s statement on spending priorities

which, though limited to a 12 month horizon for many issues, announced

with apparent pride that £4bn had been found to build 18,000 new prison

spaces. That too aroused precious little interest. It’s worth pausing over those numbers. It’s

well known that we top the European league on incarceration. While

other countries see their prison populations fall, we are planning for a

25% increase over just 6 years. To cope with that, we plan to spend an

average £222,000 on every new prison space – coincidentally not very

different from the average cost of building a new three bedroom house.

We will do that knowing that prison has the worst record for reducing

reoffending of any criminal justice intervention, and that the

government’s own estimate of the current economic cost of reoffending is

£18bn annually. One

might imagine that some of that £4bn was earmarked to replace the many

prisons that are regularly condemned by inspectors as unfit for use –

the wrong buildings often in the wrong place, costing a fortune to

maintain and to staff. But 18,000 new spaces will only cover the

projected increase in the prison population. It will not solve the

chronic overcrowding that undermines every aspect of the prison

service’s statement of purpose, from safety and security through to

decency and rehabilitation. When we’ve spent that £4bn, we’ll still be

operating overcrowded 200 year old prisons bursting at the seams, and

many thousands of prisoners will still be sharing cells that are too

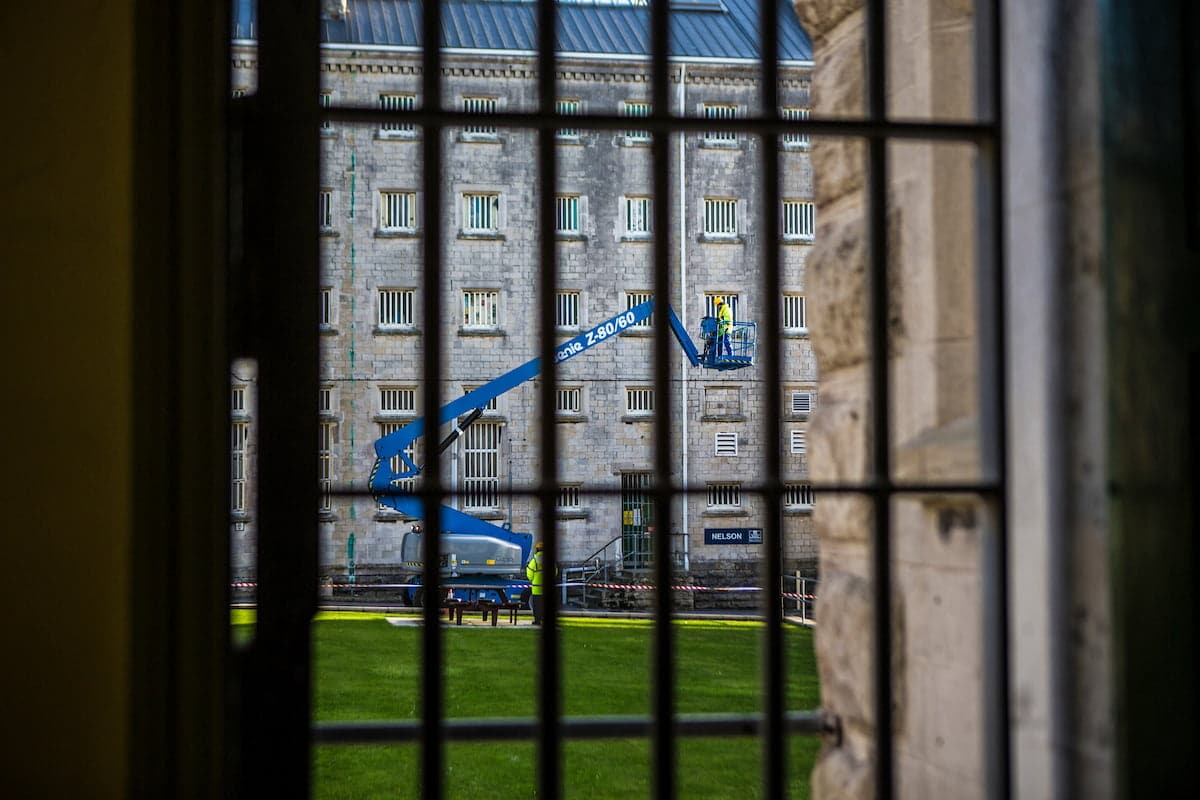

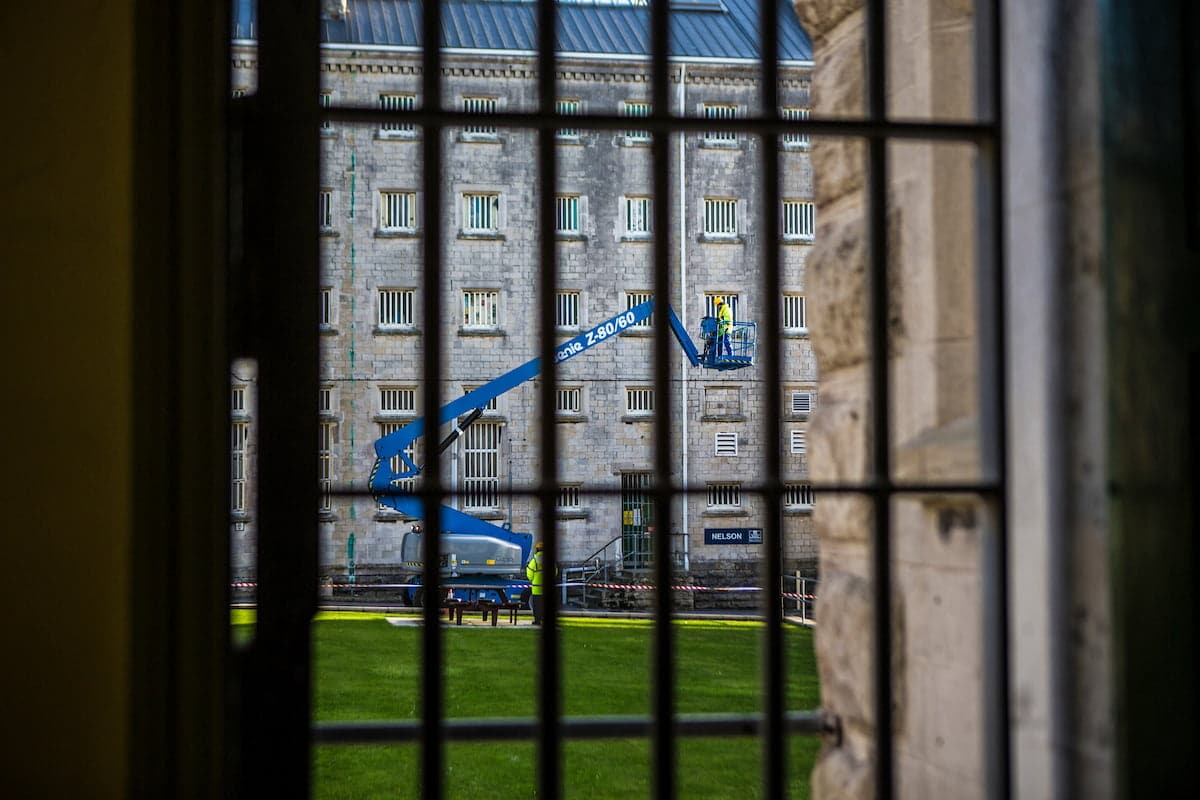

small to accommodate them. It’s like building a new motorway knowing there will be a traffic jam from the day it opens.  © Andy Aitchison © Andy AitchisonIn

the upside down world of Whitehall, this will be seen as a “good

settlement” for the Ministry of Justice. Departments that secure big

capital spending promises look like winners. But it’s actually a

testament to chronic failure. None of this £4bn comes with any promise

or expectation of an impact on crime rates, and we know previous similar

prison building programmes have done nothing to reduce reoffending. For

want of any better justification, the government has even resorted to

the argument that new prisons make sense because they boost local

economies. The

size of our prison population is not some inevitable act of fate. It’s

the product of a series of political decisions that start with the way

we support the most vulnerable in our society but finish with the way we

choose to punish people, more often than not when that support has

failed. The number of people in prison reflects the severity of the

punishment we choose to inflict, and in particular the length of time

for which we choose to lock people away. Countries with lower prison

populations are not more dangerous, and countries with higher prison

populations are certainly not safer. So

a prison population of 100,000, paid for at the cost of all the new

homes, schools and hospitals that the Chancellor could have funded

instead, is no cause for celebration. In 2017, we published an analysis

by a former Director of Finance for the prison service, that showed that

£3.7bn had been spent on new prisons since 1980. In the same

publication we were reporting record overcrowding, record levels of

violence and self-harm, but more or less identical levels of

re-offending. This Justice Secretary will be long gone by the time this

new building programme completes in 2026, but there is nothing to

suggest that his legacy will be any different. failing in rehabilitation plans there is plans to build a new prison in bucks

(20) prisonnews on Twitter: "New prison housing over 1,400 inmates could be built in Bucks https://t.co/clIwVGAmao" / Twitter

Indefinite sentences: ‘the greatest single stain on our criminal justice system’ The

problem of indefinite sentences was not going away despite imprisonment

for public protection (IPP) being scrapped eight years ago with

a former supreme court justice calling the sanction ‘the greatest single

stain on our criminal justice system’. In a foreword to a report for

the Prison Reform trust, Lord Brown of Eaton-Under-Heywood said: ‘We are

in a shocking and shaming position… . Our reputation as a just nation

demands that this IPP stain be at last eradicated.’ It

was recently reported that the family of Tommy Nicol, a prisoner who

died while serving an indefinite sentence, has received damages from the

government in an out-of-court settlement. Sentences given under the IPP

regime saw offenders handed a minimum term but no maximum term. They

had no expected date of release and many served well beyond their

expected sentence. Nicol

was two years past his four-year minimum tariff when he died in

hospital after attempting suicide in custody at the Mount prison, Hemel

Hempstead. His family brought claim against the Ministry of Justice,

arguing that the IPP sentence had constituted a breach of Nicol’s right

to life under the Human Rights Act 1998. The settlement of the claim by

the Ministry of Justice suggests some recognition of the claim’s merit

by the government. Official

estimates were that only 900 IPP sentences would be ordered when its

was introduced by Labour Home Secretary David Blunkett in 2003. In fact,

more than 6,000 people were given IPP sentences. Eight years after the

scrapping of the regime under then-Justice Secretary Ken Clarke, nearly

1,900 prisoners remain in custody under IPP sentences. Many of these are

now well beyond their original minimum term. Speaking on Radio 4’s Today programme yesterday,

one former IPP prisoner identified as Gemma (not her real name)

revealed how, despite being given a minimum term of only two years after

committing robbery, she served 13 years in prison. The delay in release of many IPP prisoners is caused by lack of availability of rehabilitative programmes in prisons. The Guardian reported that,

in Nicol’s case, evidence was to be put to the high court from

consultant forensic psychiatrist Dr Dinesh Maganty stating that Nicol

and many other IPP prisoners were ‘caught in a vicious cycle were, in

order to be released, they had to complete programmes that were not

available in sufficient numbers’. Martin

Jones, CEO of the Parole Board, told the Today Programme that people

‘need hope at the end of the tunnel’. He suggested that the Parole Board

needs greater powers to ensure that prisoners are referred to

appropriate rehabilitative programmes and suitable interventions are

made to help them progress through their sentences. IPP

sentences technically last for 99 years. This means that, even after

their eventual release, IPP prisoners are effectively monitored for life

and can be recalled for breaching the terms of their license, even if

they do not present any risk to the public. Initially released after

eight years, Gemma was recalled and served a further five years after

she was found to have smoked the synthetic cannabis, spice. She

commented: ‘Obviously, I shouldn’t have smoked spice, but I don’t think

that warrants me serving another four and a half years in prison. I

wasn’t being violent, I wasn’t out offending, the only thing that I

probably was, was a bit of a danger to myself.’ There

is a power to allow prisoners serving IPP sentences to seek the end of

their license period after 10 years. The Parole Board are reportedly

trying to promote awareness of this so that those who are eligible can

apply. Tommy

Nicol is sadly not the only recent case of suicide among the IPP prison

population. Charlotte Nokes, David Dunnings, Shane Stroughton, Kelvin

Speakman, and Steven Strudghill all died while serving IPP sentences

beyond their minimum term. The inquests into many of these deaths heard

evidence of the extreme hopelessness felt by those serving indefinite

sentences; to her family, Charlotte Nokes reportedly described being an

IPP prisoner as a death sentence. The Prison Reform Trust report documents the

trauma faced by the growing number of IPP prisoners who have been

recalled to prison even after their eventual release. The report written

by Dr Kimmett Edgar, Dr Mia Harris and Russell Webster contains new

data analysis showing that the number of IPP prisoners is not simply

diminishing over time. In fact, although the number of never-released

IPP prisoners is falling (by 57% over the past five years), the number

of IPP prisoners recalled in the same period has jumped by 184%.

Shockingly, 54% of those recalled had committed no further offence. One

prisoner interviewed by the PRT for their report gave a bleak picture

of the impact of the sentence: ‘So long as I’m under IPP I have no life,

no freedom, no future. I fear IPP will force me to commit suicide. I

have lost all trust and hope in this justice system…Each day I feel more

and more fear and dismay and I am starting to dislike life…I have to

suffer in prison in silence. Accept it or suicide. That’s my only

options left.’ The

PRT is calling for serious reforms to the operation of IPP sentences to

address some of the issues faced by both those in custody and those

released on license. As well as reducing the length of time before which

people are entitled to have their license reviewed from 10 to give

years, they recommend that the abolition of IPP sentences should be made

to apply retrospectively. This would necessitate a process of judge-led

reviews of individual IPP cases; a phased programme of releases, with

properly resourced preparation, and post-release support. They further

call for all IPP prisoners to have a fixed date on which their liability

to be recalled ends. Government should make sure that all the effort that

has gone into getting IPP prisoners safe to release is matched by a

similar effort to help them succeed in the community. Recall to custody

is a sign of failure, not success, and only makes the task of motivating

someone to try again that much harder. The continued existence of the

IPP sentence, and the worsening situation this report discloses, makes

every political appeal to our great tradition of justice sound

hypocritical. The problem is very far from being solved, and demands the

urgent attention of both ministers and parliament.’ “Inadequate treatment and conditions for prisoners with disabilities” as he hit out over standards inside the nearly 200 year old jail.Mr Taylor also warned that some disabled prisoners were “unable to shower regularly because the shower facilities were not accessible” and that 70 per cent reported feeling “victimised” by staff. PenPentonville prison condemned by inspector for failing to let inmates in wheelchairs go outside | Evening Standardtonville prison condemned by inspector for failing to let inmates in wheelchairs go outside | Evening Standard

Tommy Nicol: Family wins compensation over HMP The Mount prisoner death - BBC News Indefinite sentences: ‘the greatest single stain on our criminal justice system’ – The Justice Gap solutions@russellwebster.com Ekklesia | Number of recalled IPP prisoners in custody almost triples in five years Prison Accommodation: 4 Dec 2020: Hansard Written Answers - TheyWorkForYou * Prison Reform Trust http://www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/ Why are so many prisoners in England still serving these cruel, endless sentences? | Prisons and probation | The Guardian solutions@russellwebster.com |

|

|

|

|